BLUF

Why does this matter?

Key Take-Aways

- The President published the first directed National Security Strategy in 1987.

- The NSS is designed to adapt to changing global circumstances while promoting global stability and security.

- Between 2010 and 2016, the world experienced a time of rapid (relatively speaking) and nuanced global change.

- Strategic Competition is the current focus and may present geopolitical risk to energy companies.

Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) of the linked websites. The DoD does not exercise any editorial, security or other control over the information you may find at these locations.

Unless otherwise linked, this post is based on pre-2022 NSS archived by the Historical Office of the Office of the Secretary of Defense. The NSS are not linked throughout and can be retrieved at that site.

The President published the first directed National Security Strategy in 1987.

The Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 (Goldwater-Nichols) brought vast modifications in the Department of Defense. Section 603 of Goldwater-Nichols amended the 1947 National Security Act (now under Title 50 – 50 USC 3043) to add the requirement for an annual report on National Security Strategy. Some Presidents documented their national security strategy thoughts prior to this requirement, but the focus of this article is the Goldwater-Nichols-directed NSS.

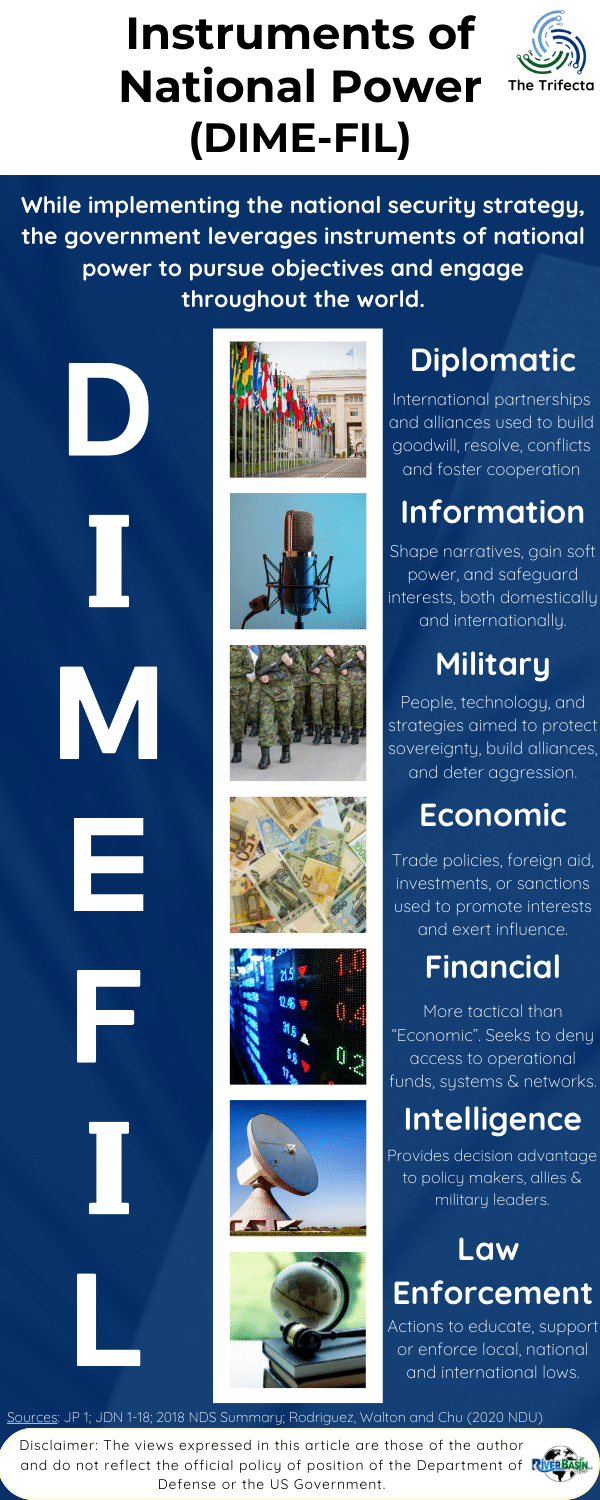

The President signs the NSS and submits it to Congress to communicate the national security vision and includes a discussion on several topics, including:

- National interests, goals, and objectives vital to US national security.

- Foreign policy, global commitments, and national defense capabilities needed to deter aggression and carry out the strategy.

- Proposed short-term and long-term uses of the political, economic, military, and other elements of the national power.

- Assessment of the US ability to execute the NSS.

Outlining a vision and strategy is only the first step in ensuring US national security. The vision communicated by the Executive Branch requires action from the rest of the Federal government to carry out the vision. Presidential administrations published the NSS nearly annually from 1987 until 2000. Since 2002, Presidential administrations more routinely published one NSS for their four-year period. Democratic Presidents have published 10 NSS (excluding the 2021 interim NSS) and Republican Presidents have published eight NSS, making a total of 18 published NSS.

In the words of the 1987 NSS, “…any strategy document is only a guide. To be effective, it must be firmly rooted in broad national interests and objectives, supported by an adequate commitment of resources, and integrate all relevant facets of national power to achieve our national objectives.” (1987 NSS)

The NSS is designed to adapt to changing global circumstances while promoting global stability and security.

This discussion focuses on the threats and goals reflected in the NSS. Major global challenges emerge over time, change, and diminish. The NSS reflects threat variability, but I simplify the contents for this introductory discussion.

From 1987 until 1991, the primary global threat was nuclear war between the Soviet Union and the United States. The goal was stability and security, which meant avoiding nuclear war. The US viewed communism as a threat and sought to promote democracy throughout the world. Building relationships with other nation states and allies was a priority. US efforts to promote the rule of law around the world highlighted the distinction between the Soviet Union’s totalitarianism and the west’s democratic leanings. Presidential administrations published four NSS during this time (1987, 1988, 1989, 1991).

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the period between 1993 and 2000 was the Peace Dividend. The Presidential administrations amended the traditional title of the NSS to include a primary focus of “Engagement and Enlargement” (1994-1996), “A New Century” (1997-1999), and “A Global Age” (2000). Global threats decreased while regional threats gained prominence. Promoting the growth of market democracies globally was the aim.

Then 9/11 happened. From 2002 until 2015, the NSS shifted focus to countering threats of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferation. The US goals included promoting freedom, human dignity, and peaceful relations among nations. Homeland defense became a priority. Presidential administrations published four NSS during this time (2002, 2006, 2010, 2015).

Between 2010 and 2016, the world experienced a time of rapid (relatively speaking) and nuanced global change.

Perception of global threats and challenges change over time and cannot be neatly cast into calendar years to meet the NSS publication cycle. The President’s 2010 and 2015 NSS are excellent examples that reflect the shifting landscape. Over time, currents events drive once-vague notions into sharper relief.

The 2010 and 2015 NSS bridged many topics from a terrorism focus to that of strategic competition. While the NSS identified violent extremism and terrorist threats as the primary threats, it expanded the scope of the discussion to articulate observations about developing geopolitical concerns.

The President discussed a “sustainable international order” in 2010 (p40), which became the rules-based international order in the 2015 NSS. Between those two NSS publications, significant geopolitical shifts occurred. Recall Russia’s invasion and annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula in 2014, a violation of the rules-based international order. At the same time, PRC started its dredging and artificial island building campaign in the South China Sea.

In 2010, the President referred to China, India and Russia as “21st century centers of influence.” By 2015, the three countries were described with additional qualifiers: India’s potential, China’s rise and Russia’s aggression. All three countries would impact the future of major power relations.

Notably, the previous 2002 NSS foreshadowed this potential change, but including the phrase “great power competition.” Following 9/11, the President sought to reframe US cooperation with Russia, India and China and noted the “possible renewal of old patterns of great power competition.” (2002 NSS p26)

Strategic Competition is the current focus and likely presents geopolitical risk to energy companies.

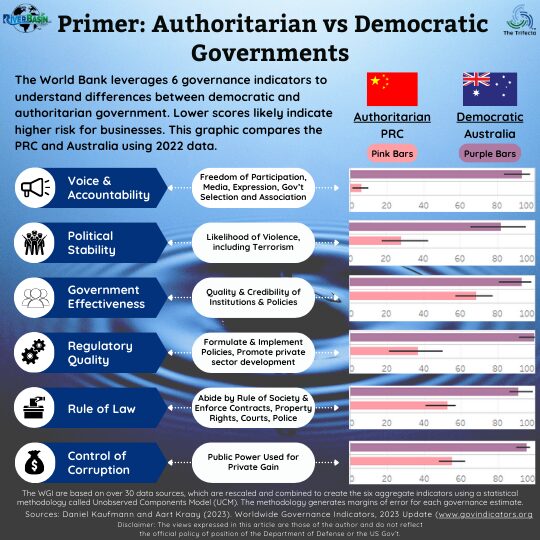

The 2017 NSS first identified the rise of competition between autocratic and democratic countries as a cause for concern, specifically Russia and PRC. (I will refer to the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) rather than China, which will be discussed in a future post.) By the 2022 NSS, the concern increased, and the President called the 2020s the “decisive decade” that will establish norms for the next era.

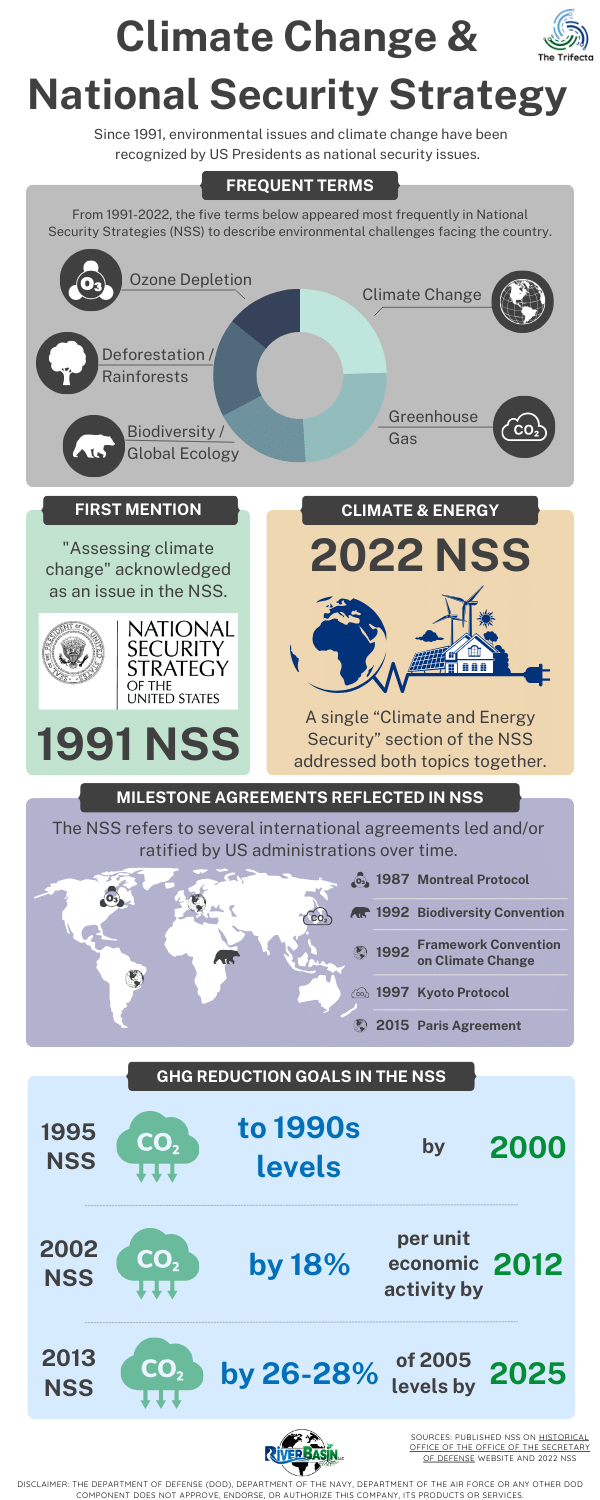

The second goal of the 2022 NSS is facing shared challenges such as climate and energy security, pandemics, food insecurity, nuclear proliferation, among others. Addressing shared challenges includes working with Russia and PRC, which complicates the geopolitical situation.

One threat highlighted in the 2022 NSS is Russia and PRC actively challenging the rules-based international order and seeking to change it to suit their goals. Strategic Competition as well as Russian/PRC efforts to challenge the rules-based international order present new geopolitical risk for business. Stay tuned for more in-depth discussion on this topic in future posts.

There is no shortage of analysis and commentary on the 2022 NSS. Consider the following for further reading – Center for American Progress, Brookings, National Institute Press, Stimson Center, American Enterprise Institute, New York Times, Foreign Policy Research Institute.

DOPSR 24-P-0111

Think About It...

- How familiar are you with the current US national security strategy?

- Who in your personal network has experience working in national security?

- How much business of your business is not local – people, processes, facilities, suppliers

Do Some Homework:

- Read pages 8-12 of the 2022 NSS to learn more about the complexities of Strategic Competition.

- For more details on the history and evolution of the NSS, see the Fall 2023 issue of the Texas National Security Review. The authors delve into political context to frame motivations behind some NSS.