BLUF

Let me be clear. This post does not advocate increased shipping in the Arctic region or minimize the myriad geopolitical challenges involved. It explores an under-represented advantage of Arctic shipping routes – avoidance of some geographic chokepoints that are geopolitical hot spots. Houthi attacks on maritime vessels in the Suez Canal, Red Sea and Bab el-Mandeb during December 2023 brought these concerns to the forefront. Arctic shipping routes avoid those hot spots (no pun intended). This post explores the potential for Arctic routes to ease geopolitical risk associated with some geographic chokepoints.

Why does this matter?

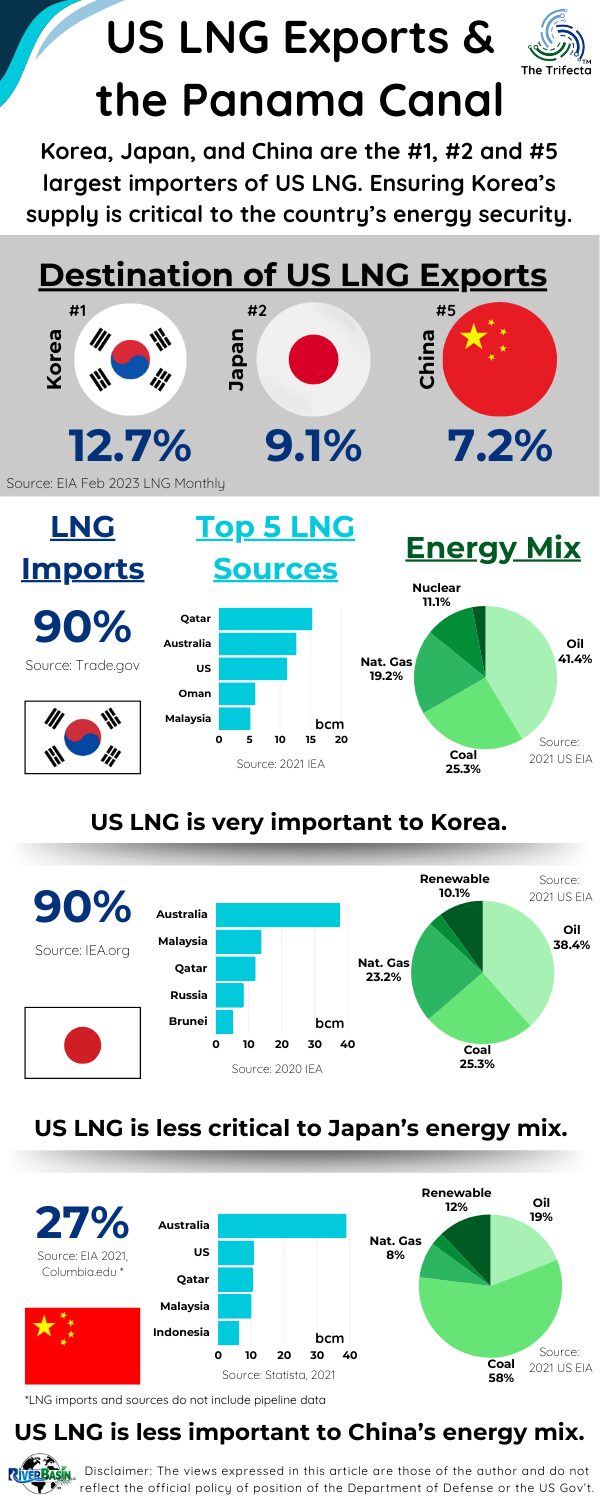

Geopolitical risk at certain chokepoints can disrupt global energy supplies, as seen in the Red Sea in December 2023. Russia leverages its Arctic route to transport oil and liquified natural gas (LNG) to Europe and Asia. This illustrates the potential of Arctic energy supply routes. Energy is a commodity industry and competitive pricing is essential. As Arctic shipping routes become increasingly available, they may present a competitive advantage for certain routes.

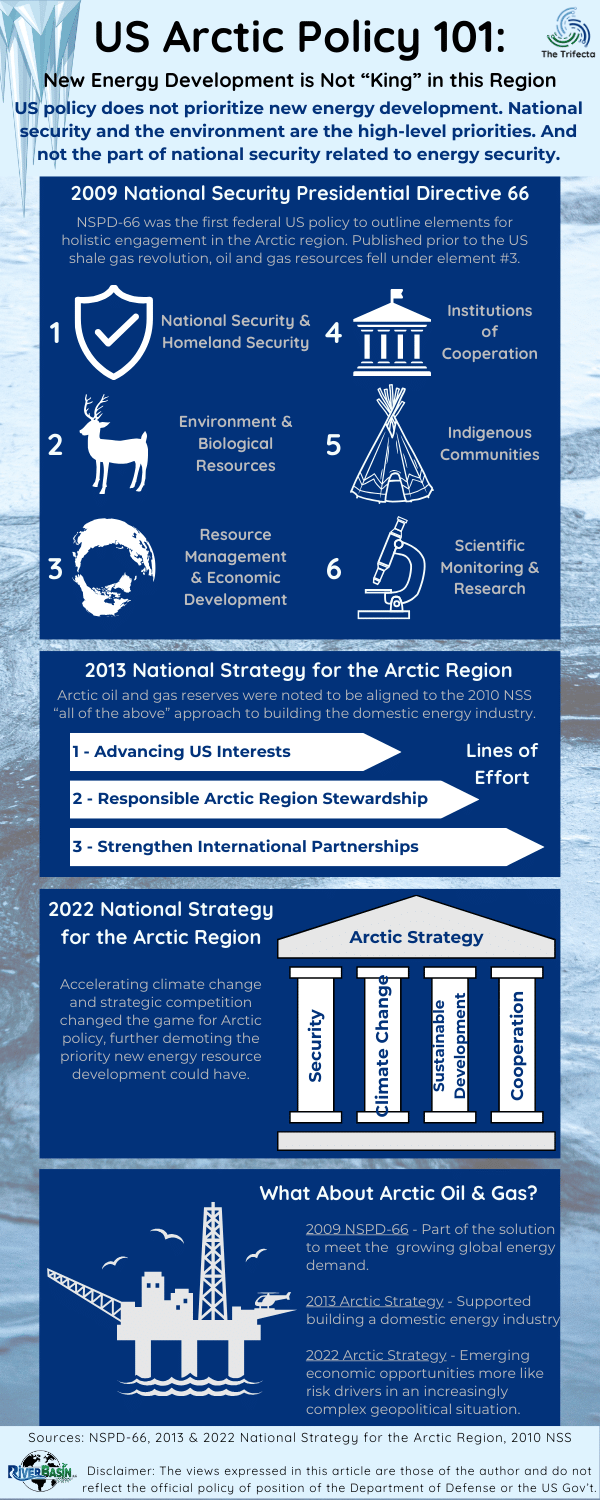

If you missed it, review the US Arctic Policy 101 post to get a refresh on US priorities. The post also covers emerging geopolitical concerns as climate change drives an increasingly ice-free Arctic and expanding shipping options.

Key Take-Aways

- Arctic shipping routes avoid geopolitical hot spots presented by some geographic chokepoints.

- But environmental and operational factors detract from using Arctic shipping lanes.

- And, the shortest Arctic route (the NSR) is controlled by Russia.

Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) of the linked websites. The DoD does not exercise any editorial, security or other control over the information you may find at these locations.

Arctic shipping routes avoid geopolitical hot spots presented by some geographic chokepoints.

Risk associated with geographic chokepoints, like straits and canals, is well known. The risk may manifest itself through human error (e.g., Ever Given in the Suez canal), climate-drivers (e.g., Lake Gatun drought affecting Panama Canal operations), or geopolitical events (e.g., Iranian or Houthi threats to the Strait of Hormuz).

A thawing Arctic raises multiple global implications. Assessments concerning warming rates in the Arctic have increased from two to three to four times as fast as the rest of the planet. Faster warming means parts of the Arctic will be ice-free during longer portions of the year. An ice-free Arctic may be more inviting for shipping, given the shorter distances compared to traditional routes.

The shorter distances are a common feature in discussions about Arctic routes compared to others. Another less discussed characteristic is the avoidance of the geopolitical hot spots along traditional routes.

Two Arctic routes already exist.

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) transits loosely around Russia’s northern border. The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the second route in the Arctic and travels around northern Canada. The ownership of both routes (NSR and NWP), is disputed, a topic better suited for legal experts.

A third route, the Transpolar Sea Route (TSP), is expected to be viable with a totally ice-free Arctic in the future. As a potential future route, the TSP will not be considered for this post.

Arctic shipping routes are not viable for oil and gas originating in the Middle East.

According to an Energy Information Administration (EIA) report in 2017, 61% of the world’s crude oil and petroleum liquids moved through maritime chokepoints (based on 2015 data). The Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Malacca ranked highest in strategic importance based on volume. See Figure 1 below from the EIA report.

EIA updated its analysis regarding the Suez Canal and Bab el-Mandab in December 2023. One notable change post-COVID occurred in early 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. European demand for Middle East oil increased because of sanctions on Russian oil. The higher demand increased European vulnerability to the two chokepoints at either end of the Red Sea. In December 2023, Maersk announced it would pause all journeys through the Red Sea. Iranian-backed Yemeni Houthis supporting Hamas claimed credit for attacking Maersk vessels headed to Israel.

Figure 1: Middle East Oil & Gas Shipping Routes

Source: EIA “World Oil Transit Chokepoints”

Looking at the map above, Arctic shipping routes would not ease risk for oil originating in the Middle East. For example, there are no sea-based shipping alternatives from within the Persian Gulf without transiting through the Strait of Hormuz. Similarly, Middle East oil destined for Europe has one primary sea-based route, which transits through geographic chokepoints. Another option is to sail around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa.

Significant disruption at these Middle East hot spots would be required to make an alternate route through the Arctic economically competitive. Today, that seems highly unlikely.

Overall, there would be no economic drivers to use Arctic routes for Middle East oil destined anywhere via sea-borne shipping. However, the Strait of Malacca is a vital geographic chokepoint linking Asia to Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

Arctic routes could provide an alternative to the Strait of Malacca to support Asia-to-Europe shipping.

Depending on the origin and destination, Arctic routes may be shorter than routes through the Strait of Malacca. For example, let’s look at the Rotterdam to Tokyo route.

A cargo ship traveling from Rotterdam to Tokyo would have three options. See Figure 2 for a depiction. The traditional route (yellow line) would be roughly 11,350 nautical miles (nm) and travel through the Dover Strait, Strait of Gibraltar, Suez Canal, Bab el-Mandab, and the Strait of Malacca.

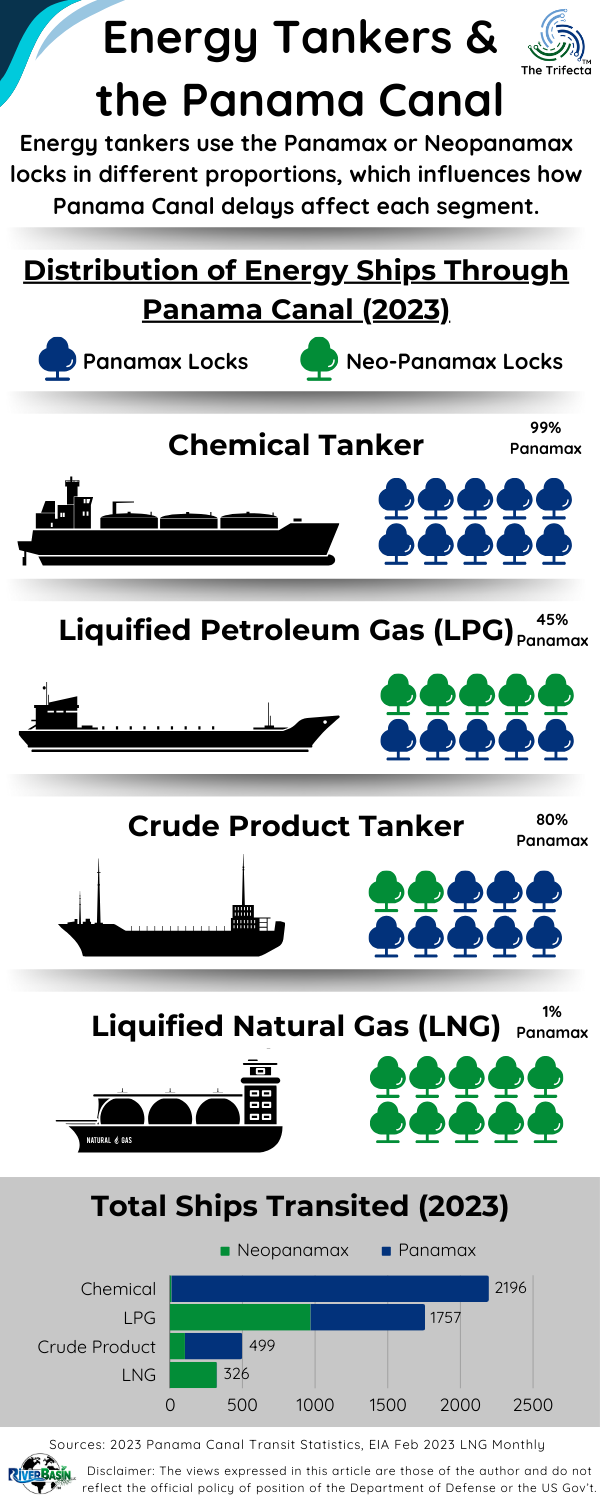

Let’s look at recent geopolitical risk related to these five chokepoints. (see infographic above)

∇ Dover Strait: About 18-25 miles (30-40 km) wide, it is the narrowest point in the English Channel between Great Britain and France. This strait does not have a history of geopolitical strife since World War II. For maritime vessels passing through the Strait of Dover, the geopolitical risk has been low historically.

∇ Strait of Gibraltar: This 8 mile (13 km) wide chokepoint separates the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. Since BREXIT, multiple diplomatic discussions among Spain, Great Britain, and the European Union remain ongoing, but these do not affect shipping. Morocco is on the south side of the strait, which sometimes raises concerns about potential access to the strait for maritime terrorist attacks. After 9/11, terrorism was a concern everywhere, including the Strait of Gibraltar. Over time, however, we did not see this strait become a favored target of maritime terrorist attacks. Illicit activity across the strait centers on smuggling humans and drugs.

∇ Suez Canal: In December 2023, Yemeni Houthis highlighted the geopolitical risk associated with shipping through this 119 mile (193 km) long and 0.14 mile-wide (225 m) chokepoint. Iranian-backed Yemeni Houthis attacked cargo and tanker ships believed to be linked to Israel. Multiple writers described ramifications for the energy industry and global trade.

The Suez Canal has not been plagued by petty maritime security issues threatening its operations. Prior to the December 2023 Houthi attacks, major geopolitically related issues at the Suez Canal since World War II related to wars with Israel. This post discusses history at a high-level only, as all Middle East or Levant history is complex.

Let’s start in 1956 with the “Suez Crisis.” This crisis contains parallels to the Houthi attacks in December 2023. In July 1956, Egyptian President Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal company, revoking ownership from the British and French. When he nationalized the canal, President Nasser denied passage to Israeli ships. This prompted Israel, Britain and France to invade Egypt to regain control of the canal. In the end, Egypt remained in control.

Next, during the 1967 Six-Day War with Israel, the Suez Canal ended up forming the front line for both sides. When a ceasefire was signed, the canal had been damaged and remained closed until after the 1973 Yom Kippur war. After the Yom Kippur war, Egypt regained control of the canal, repaired it and reopened it in 1975.

∇ Bab el-Mandab: Like the Suez Canal, Yemeni Houthi attacks in December 2023 highlighted the geopolitical risk associated with shipping through the Red Sea. Bab el-Mandab is a 16 mile (26 km) wide chokepoint on the south end of the Red Sea and connects to the Gulf of Aden.

The strait’s strategic significance increased after the Suez Canal opened in 1869 because of the massive increase in international trade flowing through this major artery. Countries surrounding the Bab el-Mandab are Eritrea, Yemen and Djibouti. Geopolitical tensions in Yemen or throughout the Middle East increases risk at this chokepoint.

The advantage of the Suez Canal is Egypt’s clear ownership and operational control of the man-made canal. It is in Egypt’s interest to maintain stability and uninterrupted transit operations. Bab el-Mandab does not benefit from the same clarity, ownership, or incentives. This increases the base level of geopolitical risk associated with the Bab el-Mandab.

∇ Strait of Malacca: At 500 miles long and varying from 40 to 155 miles (65-250 km) wide, this geographic chokepoint is the physically longest and largest covered in this post. Connecting the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean, the strait is an essential trade route for the global economy.

Figure 2: Comparison of Shipping Routes and Geographic Chokepoints from Rotterdam to Tokyo

Moving along to the other options for Rotterdam-to-Tokyo shipping. The NWP (pink line) would be 7,943 nm and transit through the Straits of Dover and the Bering Strait. The NSR (blue line) through Russia would be the shortest at 7,143 nm. Heading north from Rotterdam, the NSR avoids the Straits of Dover, making the Bering Strait the only geographic chokepoint on the route. UK government interactive maps about “Ice-Free Shipping” also show other shipping routes are shorter when re-routed through the Arctic region.

For a Rotterdam to Tokyo route, using Artic shipping routes avoids multiple geographic chokepoints that are geopolitical hot spots.

But environmental and operational factors detract from using Arctic shipping lanes.

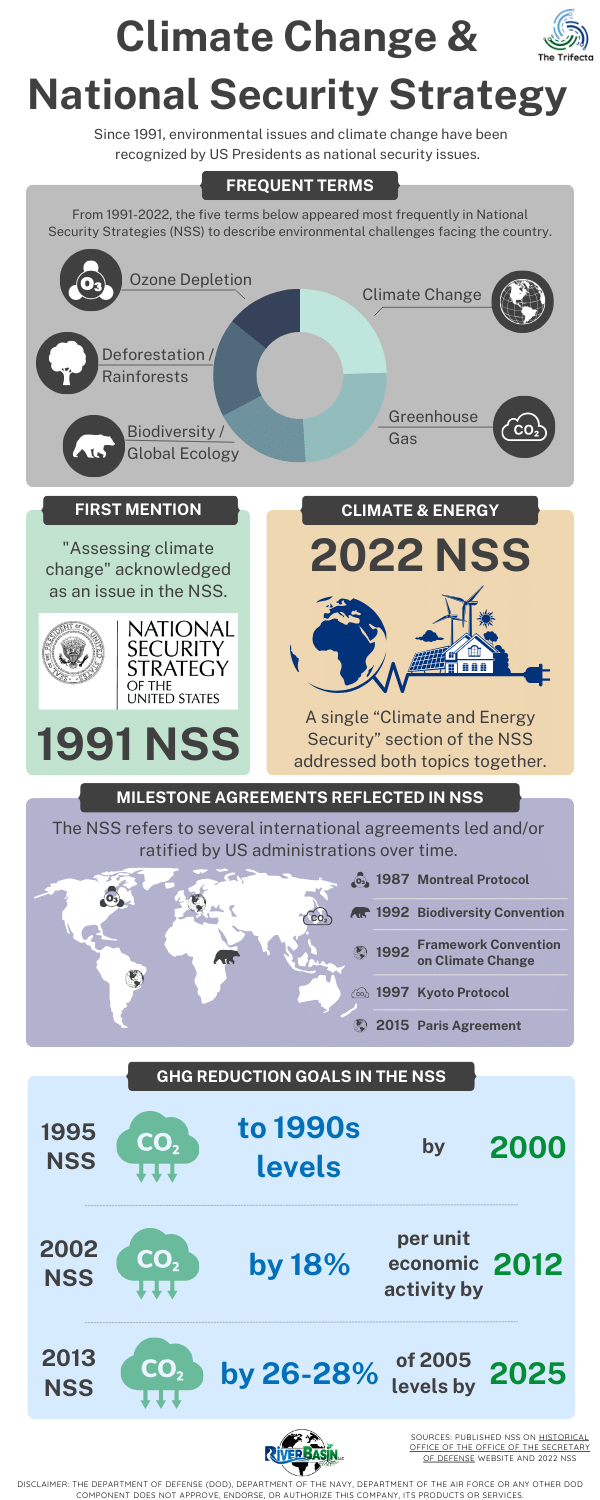

Increased shipping through the Arctic introduces additional concerns from an environmental perspective. Issues that top the list are increased emissions and particulate matter (aka black carbon), as well as effects on wildlife and the aquatic environment. Indeed, protecting the environment is a priority of US Arctic policy, which we covered in this previous post.

In January 2017, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) implemented the Polar Code, which applies to ships operating in north and south polar waters. The Polar Code includes several provisions to protect the environment, which are summarized in this infographic. Amendments prohibiting the use and carrying of heavy fuel oil in the Arctic were adopted by IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee in June 2021 and come into force on July 1, 2024. Black carbon remains an unresolved source of pollution from shipping.

Operational complications affect Arctic shipping routes

Voyages through the NSR increased by 58% between 2015 and 2019. The increased traffic provided more data about risks and mitigations. For example, insurance companies covering Arctic voyages said they add 40% to basic premiums of $50,000 to $125,000 for a single Arctic journey. They found the most common problems were equipment freezing or malfunctions, rather than the oft-assumed risk of hitting an iceberg. In addition, Arctic routes present significant logistical challenges (i.e., planning, pilots, certifications, Polar Code) as well as operational challenges when operating in 24-hour darkness. Infrastructure to support shipping routes also remains scarce.

In 2023, Li, et al, published a cost-benefit analysis of an Arctic route compared to a Suez Canal route in the peer-reviewed Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. Case studies of a Rotterdam to Shanghai route were evaluated using high-fidelity ship performance models, meteorological forecasting and a voyage optimizing algorithm. The research showed time and fuel savings for all Arctic routes, even when including insurance and other Arctic-specific costs.

Let’s not forget something – both Arctic routes include navigation through challenging geography. The Arctic routes vary and travel around and between islands. The difference is, these geographic features lack a history of geopolitical complications affecting shipping.

And, the shortest Arctic route (the NSR) is controlled by Russia.

Beyond environmental and operational concerns, there are other risks shippers would face. Rising geopolitical tensions and competition in the Artic, Russian militarization of the Arctic, and the PRC’s Polar Silk Road are just a few of the thorny concerns.

Questions about who owns the Arctic have percolated for over a decade and several countries claim territory that would be international water based on the UNCLOS. These ownership questions apply to the Arctic shipping routes, too, as mentioned above.

Use of icebreaker assistance ships and ice pilots are geopolitical-related risks associated with sailing in Russian-controlled waters of the NSR. These ships can be critical for safe operations through the Arctic region. Russia has the most capable fleet, which now includes nuclear powered icebreakers. Approved permits to travel through the NRS may indicate the requirement for ice pilots.

Russia’s control over this variable presents risk to shipping companies who may be subject to spontaneous changes in fees by Russian authorities. Recall Putin’s disregard for international rules covered in this post. Throughout 2022, Russia showed disregard for existing contracts and fee schedules, setting a precedent for this risk. Similarly, Russia could withhold ice breaker help, which is used on an on-call basis in specific escorting zones.

Think About It...

- Which energy routes would benefit most from avoiding chokepoints hot spots by traveling through the Arctic?

- How might the future renewable energy corridors differ from fossil oil and gas routes?

- Where do you expect future renewable energy “centers of gravity” will be?

- How much interconnectivity do you expect the renewable energy industry to have? More or less than the fossil energy industry?

DOPSR 24-P-0204